I was earlier thinking about my own struggles that I have had with the scapegoat complex, and the themes I wrote about regarding Dionysus, Wotan and Freyja, the Dionysian-Apollonian duality, Beyond Order and Chaos, and the linked video The Abyss: Beyond Good and Evil. Then something started to hit me, regarding how many of these themes intersect with what Nietzsche and Carl Jung were also wrestling with. From Birth of Tragedy to Beyond Good and Evil for Nietzsche or Aion and Answer to Job for Carl Jung. Next to Carl Jung’s childhood dream about Dionysus, and sensitivity when it came to Wotan. Both of them also wrestling with the concept of Good and Evil.

I also really recommend reading the article The Unseen Burden: Grappling with the Scapegoat Complex to have the proper background knowledge to fully appreciate the depth of what I am exploring in this article.

Friedrich Nietzsche

1. Victim-Child: Nietzsche’s early life was marked by significant trauma and loss. His father died when he was just five years old, and his mother, with whom he was very close, became his primary caregiver. Nietzsche’s own health problems and the feeling of abandonment and isolation could be seen as reflective of the wounded inner child. His works grapple with themes of suffering, abandonment, and a quest for meaning amidst personal pain. His later philosophical work can be seen as an attempt to transcend the limitations imposed by these early traumas, seeking to transform his suffering into a source of strength through the concept of the Übermensch. That is why he also struggled with the feminine. The inner child dealing with projective identification. Internalising ableism and guilt and shame. And feeling cut off from the love he needed as a child, splitting women into both good and bad. That is why he clung onto the Ubermensch. The strong one. It was a compensation for him.

2. Wanderer: Nietzsche’s philosophical journey also reflects the archetype of the wanderer. His concept of the Übermensch (Overman) represents a quest for self-overcoming and the search for higher meaning in a seemingly indifferent universe. Nietzsche’s constant wandering, both geographically and philosophically, reflects a search for belonging and meaning in a world where he felt alienated. His rejection of societal norms and his pursuit of a new way of being position him as a wanderer who is perpetually at odds with the culture that seeks to scapegoat the outsider.

3. Accuser: Nietzsche’s writings include a strong critique of established norms and morality, which can be seen as an expression of the inner critic or accuser. In this sense his philosophy often targets the moral and religious institutions of his time, accusing them of fostering weakness and mediocrity. Which could have been an externalisation of the inner critic within himself. Where the weakness he derided in others were really tied to the victim-child aspect that he could not accept.

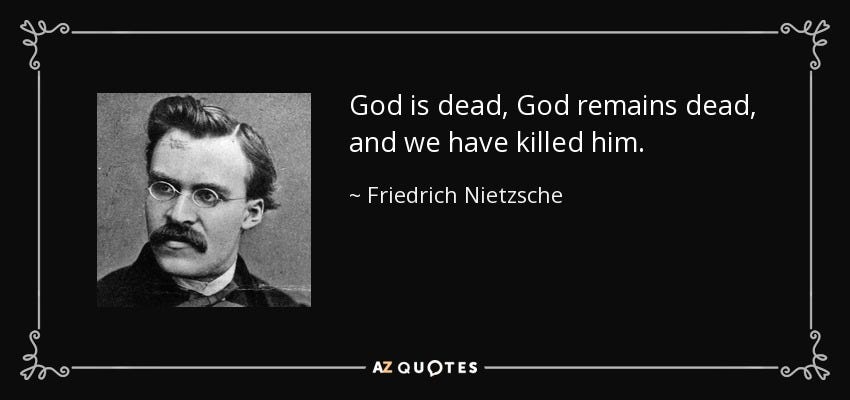

4. Priest: Nietzsche’s work can in the biggest sense be interpreted as a rebellion against the priestly figures of his time, such as religious authorities. His concept of the "death of God" challenges traditional moral and religious values, positioning him in opposition to the priestly role that upholds societal norms. However, sadly Nietzsche himself did not create a new set of moral values to replace the old ones, which might be seen as a failure to fully transcend the priestly aspect in his philosophy. Though the death of God, symbolically the Self, also ties to the emptiness the scapegoat feels in their experience. Which ties to existential angst and nihilism.

5. External Redeemer: Nietzsche explicitly rejected the notion of any form of external redeemer, be it in the form of religion, ideology, or society. His philosophy with this thus emphasized self-reliance and the creation of one’s own values. He thus sought to redeem himself internally, through the idea of the Übermensch. With this refusing the traditional role of the scapegoat who relies on external forces for salvation. So in that sense Nietzsche’s vision was more aspirational than realized. He with this envisioned the Übermensch as a potential for humanity, but this remained largely theoretical. Nietzsche himself never fully achieved this transcendence in his personal life, as evidenced by his mental collapse and his relative lack of recognition during his lifetime.

6. Internal Redeemer: Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch could be really seen as an internal redeemer figure. This figure represents the potential within each individual to transcend conventional values and create new meaning. Nietzsche’s emphasis on self-overcoming and personal empowerment highlights the role of the internal redeemer in his philosophy. Yet he was unwilling to face the victim-child.

However in the end, his philosophy remained largely oppositional. Nietzsche's declaration of the “death of God” and his critique of traditional values were indeed revolutionary, but they also left him isolated and misunderstood during his lifetime. His work did not fully resolve the tension between the forces of order (Apollonian) and chaos (Dionysian); rather, it emphasized a constant struggle between these forces.

Nietzsche’s exploration of the Apollonian and Dionysian forces was central to his philosophy, particularly in works like The Birth of Tragedy. The Apollonian for him represented order, rationality, and form, while the Dionysian embodied chaos, ecstasy, and primal drives. Where in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche critiques the binary opposition of good and evil imposed by traditional moral systems. Trying to work through the scapegoat-redeemer split, symbolized by both the Apollonian and Dionysian, as much by Good and Evil. Yet he struggled to find a stable synthesis.

Carl Jung

Jung’s childhood was fraught with feelings of abandonment and alienation. His relationship with his mother was troubled, and he experienced a profound sense of isolation. Jung's mother, Emilie, had a complex and somewhat troubled personality. She experienced bouts of depression and possibly psychosis, which caused emotional distance and instability in the family. Jung often felt that she had two personalities: one warm and loving, and the other cold and withdrawn. As a child, Jung was very emotionally sensitive and experienced intense fears at night, associating the night with his mother’s more distant, unsettling persona.

1. Victim-Child: Jung’s childhood dream of descending into the underground throne room reflects a deep engagement with his inner child and the unresolved emotional pain associated with it. The dream was a confrontation with unresolved traumas and fears in his childhood.

In this childhood dream Jung, alone at night descends stone steps and enters an underground throne room in an open grassy field through a shimmering heavy curtain of green and gold. At the end of the darkened room he sees an awesome, unknown form on a throne, illumined by a light from within. In terror and awe he realizes the shape is a huge upright living, phallos. Suddenly his mother is there at Jung’s side and cries out to the boy in contempt and dire warning–‘Yes,– just look at him, the maneater!’ Jung woke up terrified. Jung however never acknowledged that the deity of his childhood dream, that captured him for most his life, was a vision of Dionysus.

2. Wanderer: Where Jung’s journey after his break with Freud can be seen as a wanderer’s quest. His exploration of the unconscious and his visionary experiences reflected a search for deeper understanding and meaning, akin to the wanderer archetype. His period of psychological disturbance and intense visionary experiences represent his personal quest for resolution and insight into the nature of the psyche. Which also links him deeply to the archetype of Wotan and his quest for knowledge and insights into the mysteries of life. Wotan also being the archetypal wanderer.

We can see the Dionysian and Wotan influence regarding Jung further after his break with Freud. Where Jung describes a long period of psychological disturbance and a visionary experience that he described as a room full of disembodied spirits of the dead descend on him crying out “We have been to Jerusalem where we found not what we sought!” Echoing Dionysus's and Wotan’s role as communicant of the dead and his links to the realm of the underworld and death and rebirth. As the Jungian analyst Michael Cornwall pointed out, although Jung’s work has been immeasurable, it can also be said that those who went to Zurich actually or symbolically ‘found not’ what they sought because Jung disguised his Dionysian soul in Christian clothing. Which stripped it of it's deeper potency.

3. Accuser: Jung also had his share of internal struggles with his own fears and doubts, as well as his critical stance towards conventional psychological practices and theories. Which can be seen as the accuser aspect. Where Jung’s critique of the traditional view of God aligns with Nietzsche’s challenge to the more conventional moral systems in Beyond Good and Evil. Both of them advocated for moving beyond rigid moral frameworks and embracing a more nuanced and inclusive perspective.

4. Priest: Jung’s approach to psychology includes a significant influence of religious and moral frameworks, often exploring how these shape the human psyche. His work with archetypes and symbols, including the Dionysian elements, reflected a priestly concern with integrating spiritual and moral dimensions into his deeper psychological understanding. Jung’s integration of these aspects into his theories were an attempt to reconcile with the priestly role, however later in life Jung was in his letters highly critical of clerics and priestly types.

5. External Redeemer: Jung’s engagement with various mythological and religious symbols, including the Dionysian, next to his obsession with Alchemy where an initial attempt to find external forms of redemption and meaning. However he very quickly through this started to discover the Self, and thus started to reject this notion. Where he later wrote, “it’s no wonder why the westerner is so prone to devalue himself, since he’s placing all that represents goodness, even badness, but overall, completeness, outside. Even his own “salvation,” depends upon an external figure. For if there’s some kind of “salvation,” it would be more appropriate if it is self-salvation.”

6. Internal Redeemer: Jung’s concept of the Self as the totality of the psyche for him represents this internal redeemer. This is the deeper, authentic part of the self that can lead to wholeness and integration. Jung’s work also emphasizes the importance of connecting with this internal essence to achieve psychological balance and fulfilment.

Later in life closer to his death Jung examined the story of Job from the Bible, focusing on the nature of God and the problem of human suffering. He within this specific work critiques the conventional notion of a benevolent and just God, arguing that the divine realm contains both light and shadow. Jung suggested that Job’s suffering is a confrontation with the darker, more chaotic aspects of divinity, which are often repressed or denied in traditional religious frameworks. Where Jung in both Aion and Answer to Job wrote about The Divine Child archetype. Which represents both the potential for renewal and the vulnerability inherent in human and divine experiences. Jung argued that the integration of the Divine Child involves accepting the full spectrum of experience, including suffering and the divine shadow. Which is really thus about resolving the scapegoat-redeemer split.

By criticizing the dominant paradigms of his time, Jung positioned himself as a critic who saw the limitations and dangers of ignoring the unconscious. However, his ideas, particularly his exploration of mysticism and the occult, led to his marginalization and, at times, ridicule. Thus echoing the fate of the scapegoat. Jung may have approached, the complete transcendence of the scapegoat role, close to the end of his life, yet had not achieved this.

Sylvia Brinton Perera

One of Carl Jung’s students the Jungian Analyst Sylvia Brinton Perera wrote herself extensively about the scapegoat complex, and tried to work through this as well. The perversion of this archetype, was pointed out by Sylvia Brinton Perera in her work “The scapegoat complex: toward a mythology of shadow and guilt”. Scapegoat dynamics often manifest early in life within familial or social structures, where roles are assigned based on perceived differences or vulnerabilities. The scapegoat becomes a target for blame, criticism, and negative projections, disrupting their sense of self and thus contributing to a distorted self-image. This extended struggle for autonomy and the cultivation of a genuine identity characterize the scapegoat's experience. Scapegoats may be singled out due to perceived threats posed by traits such as for instance sensitivity, nonconformity, or independence.

Robin Bevan

Where I have myself built on top of the work of Nietzsche, Carl Jung and Sylvia Brinton Perera regarding this endeavour of overcoming the scapegoat complex. Where I have figured out the roles of Wotan and the Sovereignty Goddess, next to Artemis and Dionysus, in breaking down said complex. Bridging these different parts together, next to the needed rituals, informed also by the work of Sylvia Brinton Perera and her valuable insights. To create an actual pathway for other scapegoats to walk for their liberation. What I have called the Korybantic Path, where my writings on topics like Dionysus, Wotan and Freyja, the Dionysian-Apollonian duality, Beyond Order and Chaos and also my writings about the scapegoat complex are pieces of the puzzle regarding overcoming this and finding the synthesis that evaded Nietzsche.

Where I had found my answers in ancient Indo-European myths, Perera’s work and putting together the more ancient Proto-Indo-European context of the deities of Wotan, the Sovereignty Goddess, Artemis and Dionysus. My book Alchemy of the Psyche forming thus for me the theoretical backbone of my mythological and also personal exploration. As I at the same time practiced the rituals, did shamanic work connected to soul retrieval and finally in depth self-analysis. Where I finally got to the understanding I have come to regarding the steps needed to overcome this. To free oneself from these constraints imposed by the scapegoat role, and thus find my way to the Divine Child archetype that is born out of the union of opposites.