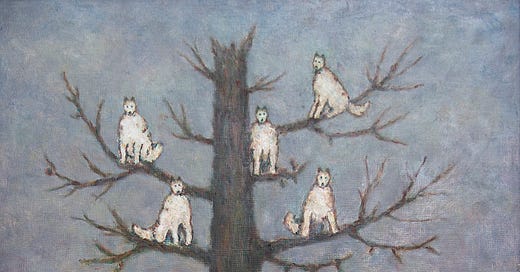

The Wolf Man's dream is one of the most famous dreams in the history of psychoanalysis. It was the terrifying childhood nightmare of Sergei Pankejeff (1886-1979), who was one of Freud’s most famous patients. The dream is so famous that Pankejeff later became known as the ‘Wolf Man’. The night before his 4th birthday, Pankejeff dreamed that he was lying in bed when all of a sudden the window swung open. Suddenly, the window opened of its own accord, and I was terrified to see that some white wolves were sitting on a big walnut tree in front of the window. Peering out, he saw six or seven white wolves sitting in the tree outside his bedroom, their eyes fixed on him. Terrified by their gaze, he woke up screaming.

Pankejeff, a wealthy Russian aristocrat, sought Freud's help for severe depression, anxiety, and neurosis in the early 20th century. Born in 1886, Pankejeff experienced a difficult childhood marked by family conflict and the suicide of his sister, which added layers of trauma and instability to his psychological development. Freud saw Pankejeff's symptoms as manifestations of unresolved conflicts rooted in early childhood experiences. Freud argued that the wolves in the dream symbolized castration anxiety. He saw the staring wolves as symbolic projections of Pankejeff’s fear of being "castrated" or punished, rooted in the Oedipus complex.

However this fails to include Pankejeff’s wish to occupy his sister’s position as their father’s favourite. Nor his parents’ declaration that he “should have been born the girl and his sister the boy”. Showing that there were deeper unhealthy dynamics at play. For instance his dad was an alcoholic, where his mother had her own issues. The nanny taking care of him instead. With the sister Anna being favoured. In that sense Pankejeff’s dream of the wolves could instead reflect the Wanderer archetype within the scapegoat complex, representing his feelings of alienation and disconnectedness. His struggles with neurosis and depression speak to a sense of lost identity, feeling aimless or “wandering” within his own mind. The wolves may also symbolize the "cut-off instinctual libido", the primal, instinctive parts of himself he felt compelled to repress or deny. Freud’s suggestion of a “primal scene” may, in this context, refer more accurately to a separation from his own primal instincts, which became externalized and projected onto the wolves. The tree could symbolize stability or family (and the Self archetype), while the wolves might represent foreboding guardians of Pankejeff’s repressed instincts or emotions. The Wanderer’s duty-bound, alienated persona, in this case, reflects Pankejeff’s inclination to carry his family’s shadows, feeling isolated by the burden of holding suppressed urges and needs within himself.

The scapegoat complex also would make much more sense regarding his later behaviour as well. He would perform obsessive religious piety. He would perform elaborate prayer rituals, and struggled against blasphemous thoughts. Revealing the inner struggle that is common with the scapegoat complex against the priest and inner accuser aspect. Pankejeff’s Priest aspect, representing internalized moral standards and societal expectations, likely enforced an unyielding spiritual code. This could have contributed to his obsessive piety and ritualized prayers as he sought to maintain a “purity” that shielded him from the “dangerous” desires symbolized by the wolves. In a sense, these prayer rituals became a way for Pankejeff to uphold the Priest’s demands for spiritual conformity and purification, which he may have internalized from family or cultural influences.

These rituals may have served as his attempt to placate the Priest’s and Inner Accuser’s (internalised familial and societal) demands and resolve his perceived inner unworthiness. The prayer routines were not necessarily spiritually fulfilling but rather a reaction to his scapegoat complex, an attempt to redeem himself in the eyes of this punishing inner voice. In this way, the Priest acted as a relentless force, urging him to maintain control over his desires and instincts by imposing strict moral behavior.

The Accuser aspect adds another layer to this, functioning as a severe, condemning voice that judged his “impure” thoughts and instincts as sinful or shameful. The intrusive blasphemous thoughts were, in effect, the very instincts and shadow desires the Accuser deemed unacceptable, manifesting in a way that defied the restrictive boundaries imposed by the Priest. The stronger the Accuser’s rejection of these impulses, the more forcefully they emerged in his consciousness, leading to his struggle against them. For Pankejeff, these blasphemous thoughts likely felt like a direct violation of the Priest’s standards (internalised familial and societal norms). He would obsessively pray, perhaps in a desperate attempt to absolve himself from guilt. However, this cyclical reinforcement of guilt and redemption only solidified the Accuser’s power, intensifying his inner critic and embedding a stronger association between his instincts and guilt.

The elaborate prayer rituals thus served as a defense mechanism, a way to cope with the overwhelming guilt and fear triggered by the intrusive thoughts. They provided him a momentary sense of control, acting as a way to "redeem" himself and maintain moral standing. But since these rituals didn’t address the root of his fears (the unmet need for self-acceptance and integration of his instinctual nature), they could not keep the inner Priest or the Accuser at bay for long. Hence why later in life he continued to struggle immensely.

When it comes to his childhood dream, the wolves, representing instinctual libido and repressed primal forces, symbolize an unacknowledged call from Pankejeff’s unconscious to connect with his inner instincts, his "internal redeemer." This is where the Koryos rite of passage offers valuable insight: traditionally, young men would enter the wilderness, symbolically becoming wolves to confront their shadow and transform it into mature, self-integrated strength. For Pankejeff, the wolf dream could be seen as a call for an analogous rite of passage, to confront and integrate the primal, rejected parts of himself in a process of individuation.

Engaging with his repressed instincts in a controlled, symbolic confrontation would allow him to address his fears and instincts directly, rather than suppressing them. This process would involve not only facing but befriending the inner wolves, releasing the hold that the Accuser and Priest had over him. As initially the cut off repressed instinct is perceived as a monstrous figure. A terrifying beast or werewolf perhaps, that is out to harm one. As often the ego is unconsciously entangled with the inner accuser and priest aspect. Hence projecting onto instinct and the shadow the judging eye of the accuser. Feeling that the eye of judgement of the accuser is omnipresent within the wilderness. The accuser akin to Azazel or another symbol of instinct becoming both the source of instinct and its source of restriction. The fear of it through projection of the accuser and priest onto that symbol creating this block.

For more insight into the scapegoat complex I also recommend this video below;