The Western Ouroboros: The Symbiotic Stage in Adulthood

Emotional Dependency and the Scapegoat Complex

In contemporary Western society, the narrative of individualism, self-sufficiency, and the lone wolf archetype is woven into the very fabric of cultural identity. From popular media to corporate ideals, we are constantly told that emotional repression is a hallmark of maturity, that strength lies in standing alone, and that one's worth is measured by the ability to give to society. Yet, beneath this carefully constructed narrative, a stark reality exists, many individuals in Western culture are still emotionally rooted in the symbiotic stage, an early phase of development where the self is inseparable from the caregiver, marked by emotional dependence and neediness.

The Symbiotic Stage and Inner Child

The symbiotic stage, typically observed in infancy and early childhood, involves a state of fusion between the infant and their primary caregiver, where emotional needs are met primarily through the external world. In this stage, boundaries between self and other are fluid, and the infant perceives the caregiver not as a separate entity but as an extension of themselves. While this phase is essential for early development, its prolonged presence in adulthood can lead to unhealthy patterns of dependency, emotional immaturity, and an inability to form authentic, autonomous relationships. In a society that values independence and the denial of vulnerability, many individuals remain emotionally stuck in this stage, unable or unwilling to confront their unmet needs or the deep sense of dependency they still carry.

However, for many, the path to true growth remains elusive because it requires more than just pushing forward. It requires an honest confrontation with the emotional wounds we carry from childhood. To genuinely evolve and experience meaningful personal growth, we must first heal the inner child, the part of us that holds our early, unaddressed emotional needs. These wounds, rooted in experiences of neglect, emotional unavailability, or unmet needs, trap individuals in a cycle of emotional dependency, stunting their growth and preventing them from achieving authentic emotional maturity. While society encourages us to "grow up" and "become independent," true healing begins when we allow ourselves to acknowledge and nurture the parts of ourselves that are still in need of care and support.

The three article series explores how many individuals in Western culture, despite outwardly adhering to the values of individualism and autonomy, remain emotionally stuck in early developmental stages, often referred to as the symbiotic phase. In this phase, boundaries between the self and others are blurred, and emotional needs are thus unconsciously projected onto the external world. These patterns, if thus left unaddressed, create a barrier to emotional growth and personal transformation. Within this first article we will cover first the basics of the ego structure and the mechanism at play, before we head in the second article into how this plays out in Western Society itself.

The Ego Structure and Scapegoat Complex

Before we head into the article itself I want to clarify some terms, to give people a basic understanding of the psychological ego structure that most operate from, which includes the scapegoat complex that Sylvia Brinton Perera wrote about.

Ego: The ego mediates between desires, reality, and social norms. Most people have a sense of ego that constantly evaluates how they appear to others. This ties into an ongoing inner narrative. A story they tell about who they are, what they’ve experienced, and how they relate to others. An ego often builds and defends a self-concept, crafting narratives about achievements, failures, or traits. The ego often judges others or projects its own traits onto them to maintain its narrative. Also being connected to a self-image, and self-consciousness. Which often leads people to feel embarrassed, awkward, or ashamed when they think they’re being judged by someone else. Many social behaviors (e.g., politeness, small talk, subtle signaling) are influenced by self-consciousness.

Neurotypical people often create self-narratives that are highly influenced by how they believe others see them, making it more externally driven. People with autism, in contrast, may not place as much emphasis on this, leading to self-narratives that are more internally focused.

Superego: The superego represents the moral and societal values internalized over time. It often acts as a critical voice, judging whether ones actions align with those values. The superego or inner critic, as it is also called, imposes societal norms about politeness, diplomacy, or sparing others' feelings. Social norms expect people to moderate their behavior based on how they’re perceived by others. Which also ties to the inner critic, what is called the inner accuser within the scapegoat complex. This is the internalised familial and societal narratives regarding the aspects that have been demonized in the culture. Which the wounded inner child feels unacceptable, unlovable and unworthy for having. There often being shame and guilt tied to this.

The scapegoat complex is a psychological and societal mechanism in which an individual or group is singled out, blamed, and cast away to carry the burden of collective guilt, fear, or undesirable traits. This is deeply rooted in myth and ritual, with the term originating from the ancient practice of placing the community's sins onto a literal goat, which was then driven out to restore order and purity. In a psychological sense, this mechanism emerges from the collective need to project shadow elements, those aspects of ourselves we find unacceptable, onto an external "other." Through this the Apollonian seeks order, structure, and purity. In its shadow aspect, this desire for control leads to the repression of emotional and instinctual energies, which are deemed threatening to societal norms. The scapegoat emerges as a product of this repression. Society identifies individuals or groups who embody Dionysian qualities, raw emotion, unrestrained creativity, or perceived chaos and casts them out to preserve the illusion of Apollonian stability. The scapegoat becomes the vessel through which Dionysian energy is symbolically released.

The act of scapegoating temporarily restores balance, releasing Dionysian energy in a controlled manner. However, this resolution is short-lived, as the underlying forces remain unintegrated. The Dionysian, being fundamental to existence, cannot be permanently suppressed. Its resurgence becomes more violent or destabilizing with each cycle, demanding true integration. By refusing to acknowledge the necessity of chaos, society creates artificial distinctions between "pure" and "impure," "civilized" and "wild," ultimately externalizing its shadow onto others.

This scapegoat complex itself is made of different aspects, as the Jungian analyst Sylvia Brinton Perera pointed out in her work on scapegoating. These aspects being the Victim-child (connected to the wounded inner child), the Wanderer, the Inner Critic, the Priest, and the Inner Redeemer. The Victim-child and Wounded Self represents the part of us that has experienced unfair treatment or emotional wounds, often from childhood. This aspect symbolizes a vulnerable inner self, which needs compassion and understanding. This aspect also relates to the wounded inner child, which symbolizes unresolved emotional pain or trauma from past experiences, often stemming from childhood.

Where the Wanderer represents the part of us that feels adrift, unsure of our purpose or direction. This inner aspect often emerges when we’re navigating a sense of disconnection or questioning our identity. In the process of searching for belonging, this part of us sometimes takes on extra responsibilities or tries to please others, hoping to be accepted. However, this desire to fit in can lead us to carry other people’s issues or overextend ourselves, which ultimately distracts us from our own needs. Both the Victim-child and the Wanderer being held away internally by the Accuser or also called the Inner Critic.

The Inner Critic is the voice inside that judges and criticizes, often harshly. It can be quick to point out flaws and may compare us to high standards or strict ideals that feel impossible to meet. This part of us may reflect societal pressures to be “perfect” or flawless, where mistakes or desires are seen as weaknesses. This inner judge refuses to accept or acknowledge any impulse. Creating thus a sort of rigid concrete block on desires which are repressed and seen as bad. Frequently, this aspect remains detached from awareness, concealed close to the inner child seeking acceptance. Which also ties into the Priest aspect, which represents our inner sense of right and wrong, often shaped by cultural, religious, or social norms. This aspect is responsible for upholding our values, guiding our choices, and sometimes even holding us to high standards of responsibility and duty. However, this internal authority can also be overly rigid or judgmental, fueling feelings of unworthiness and helplessness if we fall short. When overly dominant, this aspect might make us look to others, mentors, leaders, or even celebrities as a source of validation, hoping they’ll offer a sense of redemption.

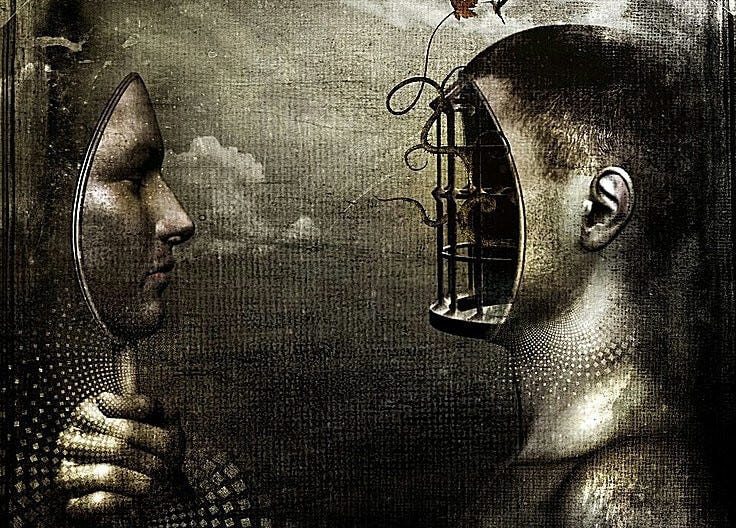

Ego Mirroring

People who are strongly identified with their ego rely on external validation for their sense of self-worth. They expect others to mirror their emotions, actions, or beliefs, reinforcing their identity and social standing. Without this mirroring, they might feel that their egoic reality isn’t being validated, which can lead to discomfort or frustration. Mirroring is something that ego-driven people typically expect: when they express emotions, opinions, or actions, they often look for confirmation or validation in others, whether consciously or unconsciously. It creates a sense of being understood and seen within their own egoic framework.

It’s often transactional, meaning people might mirror behaviors or emotions in others because they want to receive validation in return or feel socially connected to them. The interaction revolves around reinforcing one’s egoic self-concept. If thus someone expresses frustration, an ego-driven response might be to match their energy and thus mirror their frustration back, as a way to feel aligned with them. This reinforces both people’s sense of self by sharing the same emotional state or perspective, even if it doesn’t involve deeper understanding. This social mirroring is really about creating a sense of shared identity, where both people align emotionally and socially.

So when someone is in a certain emotional state (e.g., frustrated, happy, sad), this social mirroring expects one to reflect or match their emotional state. This isn't just about recognizing their emotions, but about aligning with their ego and emotional state in a way that reinforces their self-perception and social identity. For example, if someone is upset, they might expect one to feel upset as well, not just recognize their distress, but reflect it in some way so they feel understood in terms of their identity and emotional experience.

Projective Identification and Symbiotic Stage

Projective identification occurs when someone projects their unwanted feelings or aspects of themselves onto another person, but it goes beyond just projection. The other person then internalizes or takes on these projected feelings and responds in a way that reflects the projections, reinforcing the cycle. This lack of differentiation between self and other, leading to fluid boundaries, fits very well with the early developmental stage (the symbiotic stage). In infancy, the sense of self is not fully differentiated from the caregiver, and the infant sees the caregiver as an extension of themselves. This is a pre-objective stage where the boundaries between self and other are blurry. In the context of ego mirroring, this is analogous to how people, especially those more reliant on ego structures, unconsciously perceive the world and other people as extensions of their own emotional needs. So if their emotional state is not mirrored, they might feel unmoored or disoriented.

To them, this lack of emotional reflection can feel like a violation of their emotional needs or a lack of care. Their emotional state in these moments might lead them to overreact to what they perceive as emotional neglect, turning it into a sense of being victimized. So when the other person does not mirror their emotional state, if their ego is fragile or emotionally dependent, they might feel that one is withholding validation or rejecting their emotional existence. This can create an intense emotional reaction in them that might escalate into blaming one for hurting or ignoring them.

Social Mirroring

Most people rely on some degree of social mirroring to feel emotionally validated and secure. This is a normal part of human development. From a young age, people are taught to look for cues in others (especially caregivers) to understand their emotional states and how they should feel about themselves. As we grow older, this social mirroring becomes an important part of our ego, it helps form our identity and the narrative we tell ourselves about who we are. We often seek out relationships or social groups that reflect our emotional state back to us, whether we do this consciously or unconsciously. Psychologically speaking, it's estimated that a large portion of the population (around 70-80%) relies to varying degrees on social mirroring as a way of sustaining their sense of self and managing emotional experiences. This varies widely based on factors like attachment style, cultural background, and personal history.

Symbiotic Stage, Infancy and Social Mirroring

From a developmental psychology point of view, the need for social mirroring is especially crucial in early childhood. Children learn to regulate their emotions and understand their self-concept through the mirroring of their caregivers. In adulthood many typically continue to require this type of mirroring into adulthood to maintain their emotional equilibrium. The symbiotic stage refers to the early developmental phase, roughly from birth to 6-8 months, where infants perceive themselves as undifferentiated from their caregivers. This period is critical because the infant has not yet developed a clear sense of self vs. other. Psychological development ideally continues beyond this symbiotic stage, where a more differentiated sense of self begins to emerge. As children grow, they start to form an ego that can tell the difference between self and other. However, many people experience delayed or disrupted emotional development due to early trauma, attachment issues, or societal conditioning. These individuals can become "stuck" in a symbiotic-like state that mirrors the early developmental stage where their identity and emotional regulation remain heavily reliant on external validation, much like an infant needs their caregiver.

As a result, these individuals may have trouble forming healthy boundaries, maintaining differentiation between self and other, and establishing a stable ego. They are more likely to engage in projective identification, splitting, and dependency on others to regulate their emotional states, much like an infant does with a caregiver. These people might project their inner world (emotions, needs, etc.) onto others in a way that distorts reality, so projective identification, which often happens when the person doesn’t have a fully developed sense of self. They may not understand that their emotional state is theirs and thus might need to see it mirrored in others to feel validated.

The social mirroring that is so central to ego development is reinforced by external sources like family, culture, and society. These external influences shape people’s sense of self and often prevent them from developing the internalized emotional regulation and self-differentiation they need. Because many people are conditioned to depend on external validation for emotional regulation, they may never fully develop the ability to independently regulate their emotions or form a strong ego, and thus might remain psychologically in a state more akin to pre-objective infancy. The lack of development past the symbiotic stage can make it difficult for them to self-regulate and to develop an ego that is autonomous and differentiated from others. Projective identification and splitting are ways of coping with this unresolved emotional fragmentation. It is around 8 months to 3 years old, when the child realizes they are a distinct entity separate from their caregiver, often marked by the "separation-individuation" process described by psychoanalyst Margaret Mahler.

What is normally supposed to happen between late infancy to early childhood is that after the bond with the mother is created, the symbiotic phase of infancy should go towards transitional objects, such as plushies. Winnicott's concept of transitional objects and phenomena explains a phase in infancy where a child navigates the symbiotic relationship with the mother (or primary caregiver) while developing a separate identity. Positive development during this stage depends on caregivers providing consistent yet flexible boundaries, allowing the child to explore safely while feeling secure. If mishandled, this period can result in either excessive dependency or premature autonomy, both of which create challenges in emotional relationships later in life. In many cases, societal and familial influences reinforce an over-reliance on external validation. For example:

Family Dynamics: Caregivers who are emotionally inconsistent, overly controlling, or unavailable may fail to provide the secure base needed for the child to explore their autonomy safely.

Cultural Expectations: Societies that prioritize external achievements, appearances, or conformity often condition individuals to seek validation from external sources rather than cultivating a secure internal sense of self.

This reliance on external feedback to regulate emotions can keep individuals tethered to the symbiotic phase, preventing them from forming a differentiated ego and leaving them dependent on others for their sense of self-worth. Intergenerational trauma plays a significant role in this developmental stagnation. Parents who have not resolved their own emotional wounds may unconsciously project their unmet needs and unresolved pain onto their children, creating an environment that:

Fails to provide the secure attachment necessary for healthy emotional development.

Instills patterns of emotional repression, where children learn to suppress their authentic feelings to meet parental or societal expectations.

This trauma perpetuates a cycle where children are unable to fully individuate, as they are either burdened by their caregivers’ emotional needs or conditioned to avoid exploring their own emotions. When this process is mishandled:

Excessive Dependency: Caregivers who are overly protective or enmeshed with the child may prevent them from taking risks or exploring autonomy, fostering an ongoing reliance on external sources for emotional regulation.

Premature Autonomy: On the other hand, caregivers who push for early independence or fail to provide consistent emotional support may force the child to suppress their emotional needs prematurely, leading to a fragmented sense of self.

In both cases, the child is unable to develop the emotional resilience and thus self-regulation needed for healthy relationships and a secure ego structure. Within the next article we will go deeper into how this is visible within Western Culture itself, and the studies and socio-cultural signs that shed light onto this phenomena.