In modern philosophical discourse, there is a shift away from deep metaphysical inquiry towards reductionism, materialism, and abstraction. This shift, ironically, mirrors the thinking of the earliest Greek philosophers, such as the Pre-Socratics, who sought to reduce all of existence to one simple substance, whether it be water, air, or fire. In contrast, the philosophical depth achieved by Plato and Socrates, who explored the nature of truth, being, and the good, has been lost in the pursuit of logical systems and empirical evidence.

The Pre-Socratic: Reductionism and the One Substance

The Pre-Socratic philosophers, such as Thales and Anaximenes, set out to explain the fundamental nature of the cosmos by reducing it to a single substance. The ancient Thales famously posited that everything is water, and Anaximenes believed it was air. While this attempt to reduce the world to a singular essence marked a significant step in the development of early philosophy, it also began the trend of simplifying the universe to fit a neat and manageable system. Rather than exploring the depth and complexity of existence, these early thinkers sought to reduce the world to one observable, material reality.

Democritus, a Pre-Socratic philosopher, further proposed that everything in the universe is composed of small, indivisible particles called atoms (from the Greek word atomos, meaning "uncuttable"). According to Democritus, these atoms were in constant motion, and their interactions and combinations formed all matter and phenomena. This atomistic view was a significant departure from the more simplistic idea of a single substance (like water or air) being the fundamental essence of everything. Democritus' concept of atoms was, in a way, an early step toward understanding the material world in terms of fundamental building blocks, much like how modern science views the world in terms of atoms and subatomic particles.

Whether in scientific reductionism or philosophical materialism, modern thinkers have often sought to explain complex systems by isolating them to their most basic elements. This approach, while successful in some contexts, misses out on the richness and depth of the human experience, the metaphysical questions of existence, and the nature of being. Or the interconnectedness of all phenomena. As by focussing on all the parts, they don't see how the parts fit together and form the whole. Reductionism has strengths but should not be the sole lens through which we view reality.

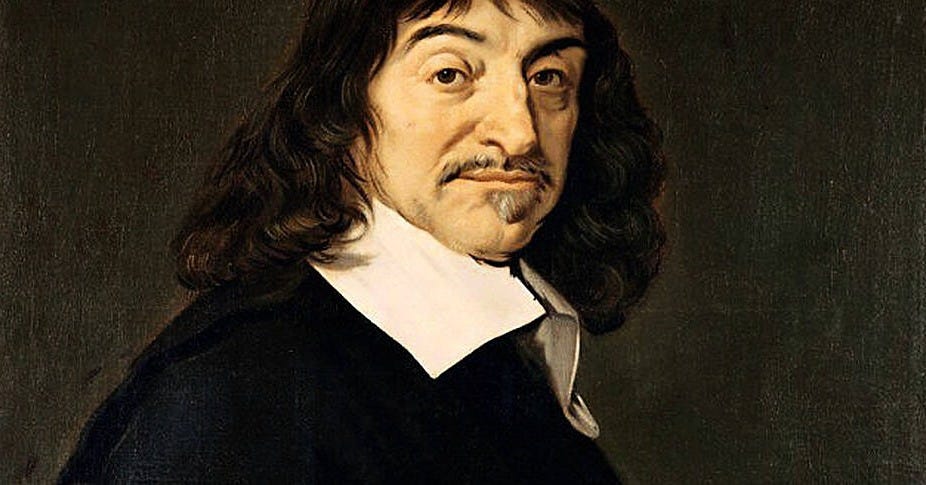

Modern Philosophy: A Return to Reductionism

In a strange parallel, much of modern philosophy has followed the same path of reductionism seen in the Pre-Socratics. Instead of questioning the nature of being itself, many contemporary philosophers focus on the material, observable aspects of reality. This trend can be seen in the dominance of empirical science and philosophical schools like logical positivism, which reduce everything to sensory data and measurable phenomena. The complexity of existence, with its metaphysical, ontological, and existential dimensions, is sidelined in favor of theories and frameworks that often neglect the deeper questions of who we are, what existence means, and the nature of truth.

Just as the early Greek thinkers simplified the world by reducing it to a singular substance, modern philosophy has reduced reality to material explanations. Whether in the form of physicalism, behaviorism, or scientific reductionism. These schools of thought may help us understand parts of reality, at best, but they fail to engage with the deeper, more metaphysical questions about existence itself. In many ways, this regression represents a retreat from the higher philosophical endeavors of the past, where the goal was not simply to describe the world, but to understand its underlying meaning.

Socrates and Plato: The Lost Depth of Being

The shift from the early Greek thinkers to Socrates and Plato marks a critical turning point in the history of philosophy. While the Pre-Socratics sought to find the fundamental substance of the world, Socrates focused on the importance of dialogue, questioning, and self-examination. He believed that truth could not be found by reducing the world to a simple concept but by engaging deeply with the complexities of human experience and understanding the nature of virtue, justice, and the soul.

Plato, a student of Socrates, further deepened this exploration with his theory of Forms. For Plato, the world we perceive with our senses is not the true world. Instead, he posited that the highest form of reality is the world of immutable, eternal Forms. Which are the archetypal realities that exist beyond the physical realm. In contrast to the reductionist view of the Pre-Socratics, Plato sought to understand the complexity of existence through the pursuit of these higher truths. His philosophy explored the nature of knowledge, the soul, and the ideal society, all of which involved transcending the material world to access deeper, metaphysical realities.

Plato’s Cave: The Shadows of Modern Thought

Perhaps the most famous symbol of Plato’s philosophical inquiry is his Allegory of the Cave, which appears in The Republic. In this allegory, prisoners are chained in a cave, facing a wall, and can only see shadows cast by objects behind them. These shadows represent the only reality the prisoners know, yet they are mere projections of the true forms. The true philosopher is like the prisoner who escapes the cave, coming to understand that the shadows are not reality but representations of a deeper truth.

Modern philosophy, however, often finds itself trapped in the shadows on the cave wall. Like the prisoners, modern philosophers may focus on the surface-level aspects of reality, the shadows, while neglecting to question the deeper truths of existence. The obsession with empirical data, scientific reductionism, and logical analysis can be seen as the modern equivalent of staring at the shadows on the wall, never venturing into the light of the deeper metaphysical questions that Plato’s allegory challenges us to explore.

The Loss of Metaphysical Inquiry

The regression of modern philosophy into reductionism and materialism is not merely an academic failure; it has profound implications for the way we understand our existence. Without a deeper engagement with metaphysical and ontological questions, we are left with a fragmented, shallow understanding of life. Modern philosophy often ignores the complexity of the soul, the nature of consciousness, and the search for meaning. Instead of pursuing the higher truths that Socrates and Plato sought, many modern philosophers are content to focus on what is immediately visible and measurable, leaving us with a world devoid of deeper purpose.

By neglecting the deeper aspects of being, modern philosophy risks becoming like the prisoners in Plato’s cave, content with the shadows on the wall but blind to the greater truths beyond. As we look to the future of philosophical inquiry, it is essential to return to the profound metaphysical questions that Socrates and Plato explored, questions about existence, consciousness, and the meaning of life. That have been lost in the rush to simplify and reduce reality to its base elements. Which aligns with the division and fragmentation of the psyche that we see within modernity. Leading to personal and collective fragmentation and division. As the modern atomic view of reality, also is connected to the dissociation and cultural psychosis that Carl Jung himself warned about could occur, if what is now deemed the meaning crisis, is not addressed. Leading to the various issues that have arisen.